The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research

Sleep apnea – are we at a treatment turning point?

For over 40 years, continuous positive airways pressure (CPAP) therapy has been improving people's sleep and saving lives. It has been a very successful treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). But it's not for everyone, and there's a growing range of alternatives.

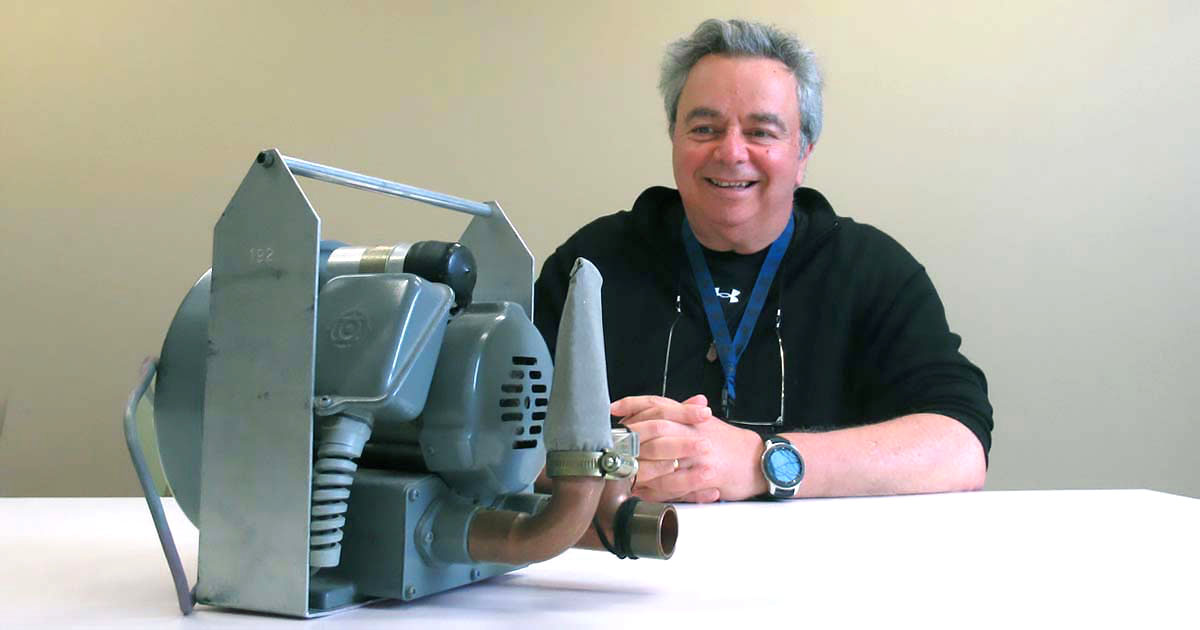

The Woolcock's Professor Ron Grunstein AM was around in the very early days of the development of CPAP as a treatment for sleep problems. We asked him about the current state of play in treating OSA, and what the future may hold.

Listen to Ron reminiscing about the early days of CPAP therapy

CPAP therapy has been described as the 'gold standard' treatment for OSA. You’ve described it as a 'tarnished' gold standard – what do you mean?

We know that CPAP is a highly effective treatment. I've been involved with CPAP for a long time now, around 40 years, and have seen the benefits for people in terms of daytime alertness, mood and quality of life. It has been a real game-changer in the treatment of OSA.

CPAP is a highly effective treatment as long as people use it. The main problem with CPAP is that many people simply can't – or won't – use it.

Some people take one look at the CPAP machine, and say 'that's not for me'. They are put off by the idea of wearing a mask while sleeping. Others try CPAP, but can't tolerate it. It is hard to wear something over your face while you sleep. It's uncomfortable. The CPAP mask makes some people feel claustrophobic. Some people pull the mask off during the night. Often this will happen during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is a really important stage of sleep.

So it's a treatment that in theory has high efficacy – it works if you wear it, but in practice not everyone can tolerate CPAP. There’s not what we call 'uniform effectiveness'.

That’s why I would say it's a tarnished gold standard.

What alternatives to CPAP are available?

There are dental devices that open up a person's airway while they sleep, a technique known as mandibular advancement. Studies we’ve done at the Woolcock show that these dental devices can be as effective as CPAP for some people.

There are electronic devices that stimulate nerves to pull a person’s tongue away from the airway as they sleep. More research needs to be done to work out if this is just a niche therapy or a more widely effective treatment.

There is surgery, in which loose tissue is cut out of a person's upper airway. Although surgery has been available for some time, it's a fairly controversial treatment, and may work better for snoring than for OSA. But in Australia we've produced data showing that some surgical procedures can be effective for certain types of patients with OSA.

There are also treatments that try to make sure a person doesn't sleep on their back. As many long-suffering sleep partners will know, our snoring is usually worse when we sleep on our back. There's a device on the market that vibrates if a person moves into what we call a 'supine' posture (on their back) during sleep. The device wakes them up, so they move onto their side. The waking is very transient, so it doesn't really disturb sleep. It's not a therapy for everyone, but it works for some people.

There's also a big growth in drug repurposing for the treatment of OSA. For example, an anti-epileptic drug is currently being trialled for its effectiveness in sleep apnea. Other drugs that affect upper airway muscle activity are also being trialled.

Wakefulness promoters, or drugs that keep you awake, are also being tested. It looks like these drugs help with the symptoms of sleep apnea, but don't really change the underlying severity of the condition.

And then there's a very promising line of inquiry that our team at the Woolcock is investigating – the use of weight loss drugs in the treatment of OSA.

We know that obesity and OSA are related. Although the relationship is complex and may involve a variety of factors – such as a person's facial structure – research shows conclusively that being overweight or obese is a key risk factor for sleep apnea.

Our team is now part of a global trial to test a drug originally developed for diabetes that is very effective in reducing a person's weight. We want to know if the drug can also be effective in treating sleep apnea in people who are overweight.

It's an exciting line of research. The Woolcock did a study more than ten years ago showing that when you start to get substantial weight loss, you start to get quite marked reductions in sleep apnea. But of course, weight loss is not easy: it needs to be sustained over the long-term, and is easily thwarted by changes to lifestyle, exercise, diet, physiology, and environmental and social influences.

Want to stay up to date with our research on sleep conditions?

Sign up to our monthly newsletter

Which alternatives do you think are the most promising? Do you think any alternative treatment will become the new gold standard?

As you can probably tell from my previous answers, treating sleep apnea is highly personal. There’s no universal 'fix' for sleep apnea: different people react in different ways to different treatments. So I would be surprised if any one treatment becomes a 'gold standard' for everyone.

But I'm very excited about our research into weight loss. In the Woolcock's earlier study, we found that when you're very successful with weight loss – for example, a sustained 15 percent loss in weight – most patients' sleep apnea goes away or at least becomes very mild.

In a recent landmark New England Journal of Medicine study, the drug we're testing delivered on average 20 to 25 percent weight loss in non-diabetic people, so we think it's going to be a game changer in sleep apnea.

In future, weight loss is likely to become a significant treatment for OSA. I know others working on the international study share my excitement – like me, they get a sense that this is going to be something that will bring huge benefits to many people.

On the other hand, we need to be cautious. It would be a tragedy if clinicians and patients abandon sleep therapies that could work for them – such as CPAP – for a 'quick fix' of a weight reduction pill. We always need to take a multidisciplinary view to treating a person's OSA. We need to make sure we consider multiple therapies.

If I'm on CPAP, is there anything I can do if I want to try an alternative?

First, I think it's important to say that if CPAP is working for you – if you're sleeping OK, you don't really have any complaints, and you’re tolerating your CPAP therapy – I'd probably do nothing. The treatment is working.

However, if someone is not happy with their CPAP, or just can't use it, then I think they should be reassessed, especially if it's been a few years since they talked to their doctor about it. Treatment is always changing, so there may now be other therapies that that are more effective for them.

If they can get a referral to a multidisciplinary specialist sleep centre such as the Woolcock Clinic, they’ll benefit from all the different expertise that it takes to diagnose and treat OSA – not just sleep specialists, but also dietitians, psychologists, ENT surgeons, psychiatrists, dentists, and neurologists. Patients may even be able to take part in trials for one of the new alternative treatments we're researching.

I get a sense we could be at a turning point in our use of CPAP. Over the next five years I think there's going to be some interesting developments in the management of sleep apnea. It's an exciting time to be involved in researching the alternatives. Almost as exciting as 40 years ago when CPAP was first being developed.