The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research

Show me the data: supporting medication adherence

How do community pharmacists calculate or estimate their patient’s medication adherence to determine whether they need support? How do estimates change if different data are made available? What data sources would enable pharmacists to offer the best support?

Researchers Sarah Serhal, from the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, and Dr Anna Campaign, from the George Institute, consider the benefits and limitations of the two major data sources.

Pharmacists act as a unique safety net within primary care, often wearing many different hats in a single day. One of these hats is identifying which patients need medication adherence support, and why.

Pharmacists can identify patient specific adherence barriers, identify unnecessary therapy escalations, and effectively triage patients struggling with adherence to appropriate care by their clinicians. This is made easier with the right information. Understanding how this can be achieved more effectively is paramount.

The wider problem is maintaining optimal adherence. This is a challenge regardless of the medication or the nature of the illness.

The World Health Organisation in recent decades has estimated long-term medication adherence for chronic conditions to be less than 50 percent. This estimate has remained consistent over the past 50 years, however is likely to become greater as the global population ages.

Poor adherence not only negatively impacts a patient’s health and reduces the effectiveness of treatments, it also contributes to an increased financial burden on patients and the health system.

For pharmacists to assist patients, they must first identify those who need support. But how do community pharmacists calculate or estimate their patient’s medication adherence? How do estimates change if different data sources are made available? And what data sources would enable pharmacists to best support their patients?

Understanding adherence

To answer these questions, adherence needs to be understood. Adherence is estimated based on the amount of medication provided (or purchased) over time.

Different methods of measuring adherence exist but each have three required elements:

- how much medication was dispensed;

- when was the medication dispensed; and

- how quickly will a patient complete a single supply of medication.

If any of these components are missing, assumptions such as those described below need to be made.

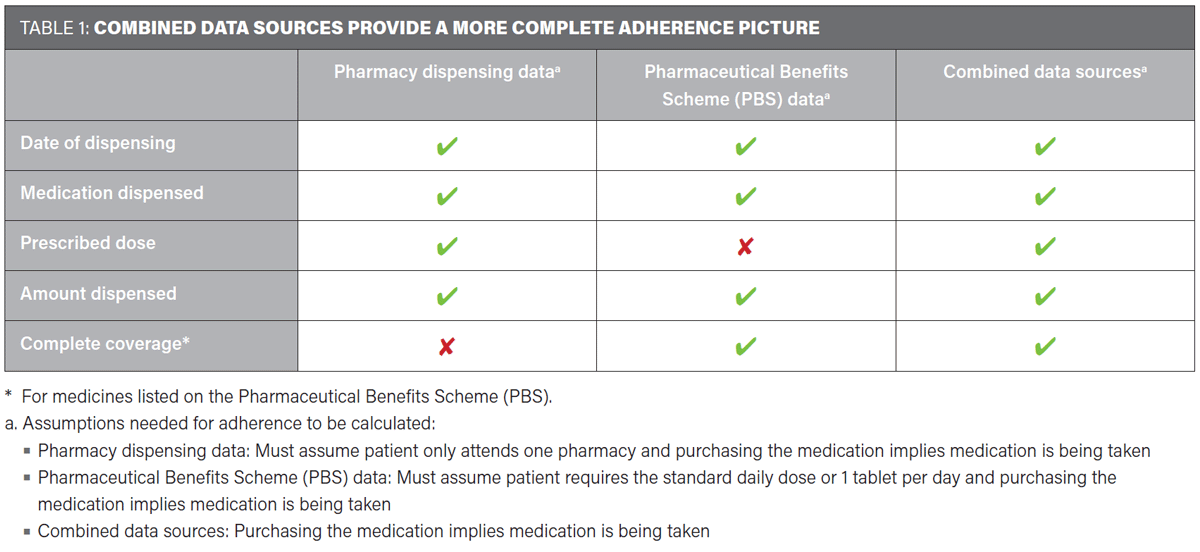

In Australia, there are two major data sources for medication dispensing:

- Pharmacy dispensing data, which is generated at individual pharmacies.

- Data generated through the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS).

Pharmacy dispensing data is a valuable source of information, and for each dispensed medication usually includes the date, amount and type of medication dispensed, and the prescribed dosage. However, pharmacy dispensing data has limits, as it is only available for the pharmacy that generated the data. If a patient goes to multiple pharmacies, each of the attended pharmacies capture a separate piece of the patient’s dispensing history.

PBS data also includes the date, the amount and the type of medication for each dispensing. Although the data source has complete coverage of all PBS prescriptions dispensed nationwide, it does not contain any prescribed dosage information. Researchers using PBS data for adherence calculations use standard daily doses as a proxy for prescribed dosage. Yet something as common as pill splitting highlights the inadequacy of these assumptions.

When the two data sources are combined, the gaps in each data source are filled. Therefore, it is only when they are combined that the assumptions being made in adherence calculations can be validated (see table 1).

The value of combining data

In one of our recent studies, we considered adherence to asthma controller medications. When medication adherence was calculated based on pharmacy dispensing data alone, 80 percent of patients appeared to be struggling to some degree with their adherence. But when the PBS data alone was used to calculate adherence, only 66 percent were having difficulties with adherence.

When both data sources were combined, likely to be the most accurate estimation of adherence, it was estimated that 70 percent of participants were struggling with controller adherence.

Interestingly, the patients who appeared most adherent were those, at least in this study, going to multiple pharmacies. If pharmacy dispensing data alone was used to identify the patients in need of adherence support, potentially adherent patients could have been identified.

With healthcare becoming increasingly digitalised, leveraging the integration of My Health Record into primary care and community pharmacies could provide access to both the complete claims history of a patient as well as the prescribed dosage for a medication.

Although currently there are limitations in accessing My Health Record data, when access has been safely and appropriately established, combining this with the pharmacy dispensing data could close information gaps, allowing for a more accurate understanding of a patient’s medication adherence.

Providing access to the wider dispensing history of patients would create centralised data access for pharmacists. The advantages of this can be extended to assist in other therapeutic areas and chronic conditions.

In particular, real-time monitoring of a patient’s opioid use and oversight of doctor and pharmacy shopping practices could have positive implications for drugs of addiction or abuse.

Data can only help to a point. Purchasing medications will not guarantee that the patient takes the medication, and access to even the best data is no replacement for individualised care.

Want to stay up to date with our work on asthma, hay fever, COPD and other respiratory conditions? Sign up to our monthly newsletter

The critical decisions

It is critical that efforts to identify less than optimal adherence should be combined with a general review of the patient as well as non-judgemental interviews to assess the risk that non-adherence may pose for the patient.

Practical tools for the patient are often available that can be used to assist in taking medications on time. Sometimes it may be appropriate for a referral to a clinician where further care or therapy simplification is required.

Pharmacists have the ability to engage and motivate patients to make informed decisions about their medication management, so it is important to engage patients and help to create patient-centred solutions at every opportunity granted.

When big data is allowed to inform local data, Australian pharmacists will have the best seats in the house to accurately measure patient adherence and mitigate risks of poor adherence.

The time is ripe to reflect on opportunities to use data to better serve the community and individual health outcomes.

Further work is needed by the Australian pharmacy community to realise the full utility of centralised datasets in community pharmacy practice, with automated systems and specific frameworks to be developed to facilitate this. This will allow integration with workflow and software to optimise health benefits and at the same time safeguards patient privacy.

We could perhaps become an encouraging example for other nations to follow.

This article first appeared in the Australian Journal of Pharmacy, August 2022.

Find out more

- Read research article Integrating Pharmacy and Registry Data Strengthens Clinical Assessments of Patient Adherence, Frontiers in Pharmacology, March 2022

- Sarah is part of our Clinical Management Research Group

- More about asthma and our asthma research